In Africa’s most fragile states, entrepreneurship often begins not with opportunity, but with necessity. In South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), instability is part of daily life: insecurity on the roads, unreliable electricity, inflation that wipes out savings overnight. On top of this, social norms often discourage women from leading, adding another barrier to entrepreneurship. Yet amid these conditions, young entrepreneurs are carving out spaces of resilience. Their businesses are not just livelihoods, they are acts of defiance, of creativity, and of hope.

Through the stories of three Orange Corners South Sudanese entrepreneurs: June Owdo Joseph Ojukwu (Pure Organic South Sudan Honey), Duom Peter Chol (Junub Kids), and Ajah Jennifer (Yommie Co. Ltd), and the broader perspective offered by Lucien Azmayawa, Orange Corners DRC, hub manager in Goma we see how entrepreneurship becomes more than business. It becomes a means for dignity, stability, and even social cohesion.

June Owdo Joseph Ojukwu: honey and hope in a bitter context

June Owdo Joseph Ojukwu started her honey company, Pure Organic South Sudan Honey, in Juba in 2019, driven by a vision to turn a simple, natural product into a sustainable business. Her company sources raw honey from smallholder farmers, supports them with training and tools, and then processes, packages and sells the honey under her own brand in South Sudan’s capital Juba. What began as a modest initiative quickly grew into a supply chain connecting rural farmers to urban markets.

Within a year, the COVID-19 pandemic struck. Borders closed, movement was restricted and supply chains froze. For many young entrepreneurs it would have been the end, however June adapted. “We found out that honey can support people who are having a cough,” she explained. “So even if we did not make profit, we sold what we had at an affordable price, delivering it door-to-door.”

This instinct to adapt has defined her journey. Today, she leads a team of nearly ten employees, most of them young women. Through her network, she supports dozens of farmers with tools and supplies. They deliver raw honey, which her team processes, packages and sells in Juba.

Yet the challenges are relentless. “On the road there are armed people who collect money at roadblocks when transporting more than 2 jerrycans of honey. If you don’t pay, your honey can’t pass,” she said. Economic instability and insecurity inflate costs and create constant uncertainty. June explained that even harvests aren’t safe, as thieves sometimes raid beehives before the season ends.

June has responded by diversifying. Instead of relying on one region, she now works with farmers in three states, ensuring that a disruption in one area does not collapse her entire supply chain. She also empowers farmers themselves to negotiate with local drivers and checkpoints, leveraging community ties to reduce arbitrary fees.

Beyond logistics, June faces cultural barriers. “People tell me I am not a good woman for being in the market doing business. They assume I must be acting indecent.” But training, mentorship and sheer perseverance have given her the strength to be resilient and ignore the stigma.

Her vision is bold: to establish her own honey farm on land she recently procured, reducing transport costs and creating jobs in the community. “I need to see my product around the world,” she says, imagining her organic honey on hospital shelves, treating wounds and coughs.

June’s story is one of persistence: of finding sweetness in a bitter context, and creating dignity and opportunity where fragility threatens to dominate.

Duom Peter Chol: books born of loss

For Duom Peter Chol, entrepreneurship was born of grief. In 2020, his wife was diagnosed with kidney failure. As they sought treatment in Egypt, the family and well-wishers struggled to pay for both dialysis and their daughter’s education. Unable to afford preschool fees, they tried homeschooling. But when Duom Peter looked for English books suitable for her age, he found none.

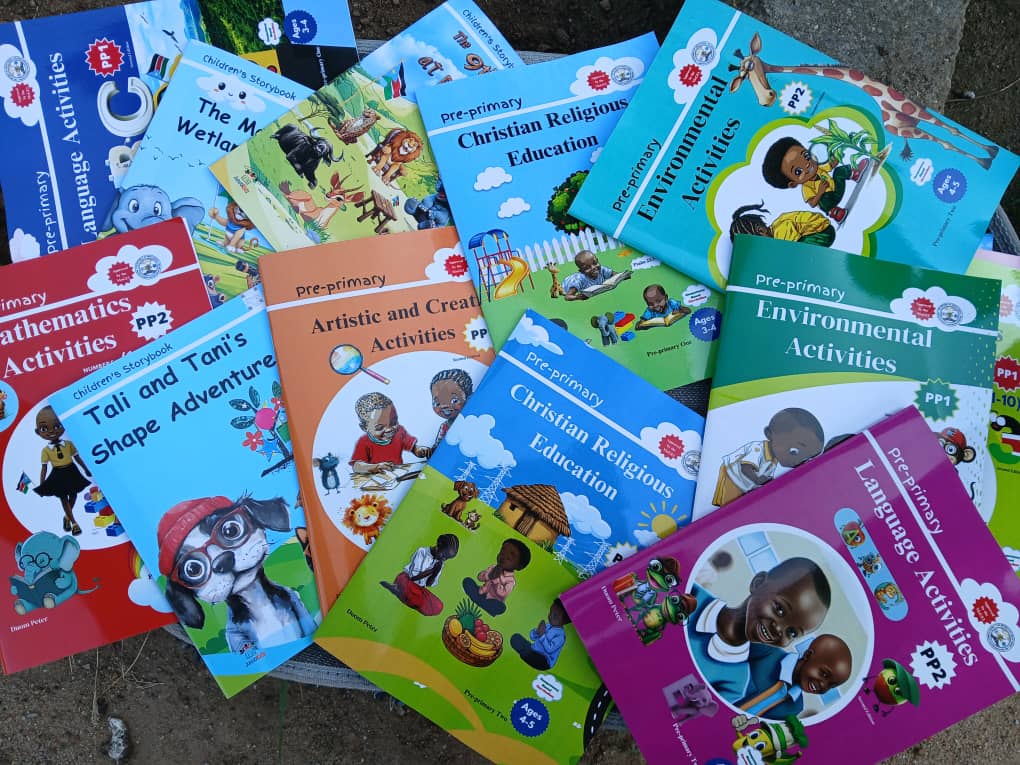

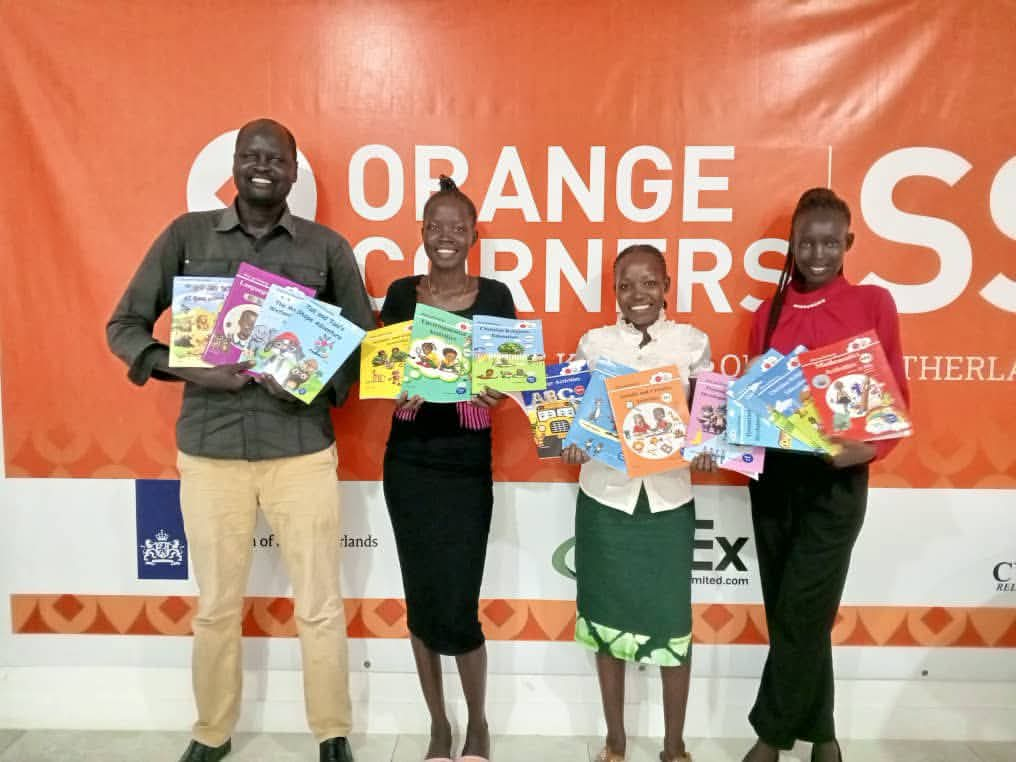

It was his wife who suggested the solution. “Why don’t you write them yourself?” she asked. A teacher by training, Duom picked up a notebook and began drafting stories for children. Over the next year, he wrote fifteen books aligned with South Sudan’s pre-primary curriculum. Before she passed away, his wife saw only the beginnings of this effort, but her words planted the seed for what became Junub Kids.

Back in South Sudan, Duom Peter presented his books to the Ministry of Education. They reviewed and accepted them. Soon, his books were in classrooms. Today, Junub Kids titles are used in more than 200 schools, reaching over 32,000 children, which is a remarkable feat in a country where 94% of preschool-age children are out of school.

But building an education company in South Sudan is not easy. “Printing books is extremely expensive here. I have to go to Uganda, where it is cheaper,” he explained. Even then, inflation and rent hikes make sustainability fragile. To cope, he moved much of his sales online, posting on Facebook and delivering books directly to schools.

The banking system adds another layer of instability. “If I deposit one million South Sudanese pounds, the next day I may only be able to withdraw the equivalent of five or ten US dollars,” he said. To protect his company, he converts earnings to dollars as quickly as possible.

Despite these obstacles, Duom Peter’s motivation is unwavering. “The situation in South Sudan looks complicated, but we should not run away. We must address these challenges, and the money will follow.” For him, education is not just a business; it is a way to rebuild the country. “If we address the lack of teaching materials, South Sudan will move to the next phase.”

Junub Kids is more than a publishing house. It is a tribute to his wife’s vision, a legacy for his daughter, and a lifeline for tens of thousands of children. Each book carries not just lessons in reading and writing, but a quiet reminder that out of personal loss can come a collective gain.

Read more about Junub Kids here.

Ajah Jennifer Mayen: dignity in every period

For Ajah Jennifer Mayen, entrepreneurship is inseparable from her own life experience. As a young girl growing up in South Sudan, she experienced period poverty firsthand: the shame, discomfort and missed opportunities caused by a lack of access to sanitary products. “Every day you hear terrifying stories about girls sitting in water during their menstruation because they have no other choice,” she said.

Her company, Yommie Co., is tackling this head-on. Beyond producing affordable sanitary products, she is building a movement: raising awareness about menstrual hygiene and training mentors to teach younger girls in schools. “It’s not just about products. It’s about dignity.”

But she faces the same storm of economic turbulence. Severe inflation makes it nearly impossible to set stable prices. “We want to sell below one dollar, but inflation pushes us higher. Many girls simply cannot afford it,” she explained. Policy shifts and taxation create further uncertainty, changing overnight with government reshuffles.

Ajah Jennifer’s solution is to localise production. By manufacturing sanitary products within South Sudan, she hopes to control both quality and price, insulating her company from the shocks of import costs. She is also piloting community trainings and campaigns tied to international awareness days, building both markets and momentum.

Her vision stretches beyond hygiene. “In five years, I want to incorporate support for women’s mental health and trauma. Periods are just one part of our struggle. Women carry invisible wounds too,” she said. Ajah Jennifer’s enables girls to attend school without shame, she not only addresses a health need but invests in South Sudan’s future.

Lucien Azmayawa: building ecosystems amid chaos

While entrepreneurs like June, Duom Peter and Ajah Jennifer fight daily battles to keep their businesses alive, Orange Corners hub managers like Lucien Azmayawa in Goma, DRC, focus on building the conditions that allow them to grow.

Lucien manages Wakisha Holdings, an incubation hub offering training, mentorship and networking and implementing partner of Orange Corners in Eastern DRC, where conflict and instability are daily realities, such hubs are lifelines. “Our mission is to strengthen the capacities of young entrepreneurs so they can grow viable businesses, even in a fragile context,” he explained.

The challenges are immense. In Eastern DRC, overlapping authorities mean that business documents issued in Goma are not always recognised nationally, making expansion nearly impossible. Banks barely function, forcing reliance on mobile money, where exchange rate fluctuations erode earnings. And when entrepreneurs are forced to keep cash on hand, entire assets can be wiped out in a single robbery.

Even daily operations are precarious. During one recruitment process for a new cohort, simultaneous outages of electricity, internet and water paralysed the city. The hub relocated to a hotel to complete its work. “You must be able to react quickly, find alternatives and maintain quality in an unpredictable environment,” Lucien said. This same instability pushes entrepreneurs in Goma to find their own solutions: some move to coworking spaces to reduce costs, while others relocate activities to safer cities like Beni. Digital platforms have opened new markets abroad, insulating businesses from local instability. Collaboration is also rising, with startups pooling resources or co-creating ventures.

What gives Lucien hope is this creativity. “Despite the challenges, young entrepreneurs constantly find innovative ways to move forward. There is enormous potential here, ready to be unlocked with the right support.”

Entrepreneurship as social cohesion

South Sudan and the DRC are often described in terms of fragility, instability and crisis. But listen closely, and a second narrative emerges: one of determination, creativity and belief in a better future. The stories of June, Duom Peter, Ajah Jennifer and Lucien show that entrepreneurship in fragile states is more than survival. It is resilience made visible, creativity under pressure and hope embodied in business models.

At the individual level, entrepreneurs are not just earning incomes: they are reshaping norms. June defies cultural expectations by leading a company of young women in a patriarchal society. Duom Peter turns personal tragedy into opportunity, challenging South Sudan’s literacy gap with locally written books. Ajah Jennifer confronts the stigma of menstruation, giving dignity to girls who for too long have been denied it. Each of them is reshaping the social fabric in small but powerful ways. At the ecosystem level, hubs like Lucien’s provide structure amid chaos, enabling entrepreneurs to learn from each other, share resources and access markets.

Hubs like Lucien’s in Goma offer something just as vital as training or mentorship: stability in an unstable environment. They provide entrepreneurs with community, structure and continuity when everything else feels uncertain. A WhatsApp group or a shared co-working space may seem simple, but in fragile contexts they can be lifelines and places where information circulates, trust is built and ideas turn into collaborations.

Moreover, at the societal level, the ripple effects become visible. Jobs reduce the lure of violence. Affordable books and sanitary products build futures beyond conflict. Networks of entrepreneurs demonstrate that inclusion and social cohesion are not abstract ideals but lived realities. Each entrepreneur becomes a point of light in environments too often defined by shadow.

Orange Corners’ role here is not to overshadow these local efforts but to enable them to grow. By offering training, mentorship and funding, our programme strengthens the capacities that are already present. It gives entrepreneurs the tools to withstand shocks and the networks to amplify their impact. In doing so, Orange Corners helps transform isolated acts of resilience into something systemic, which is a kind of social infrastructure for stability.

Supporting entrepreneurship in fragile states is therefore not charity. It is an investment in a different trajectory: one where local talent and creativity become engines of cohesion and progress. The stories of June, Duom Peter, Ajah Jennifer and Lucien remind us that fragility does not mean hopelessness; it means there is more at stake, and more to gain when people are empowered to act on their ideas. With the right support, entrepreneurs in fragile states are not only surviving but transforming their communities, and laying down foundations for stability and a future built on possibility rather than precarity.